Last week I checked out two very different books from the Woodstock public library with the hope that I could use one in order to understand the other. One of the books was Jack Kirby’s Captain America Bicentennial Omnibus and the other was Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.

You’d think that my growing up in the 70s would’ve put to rest any inclination to pursue Freudian theories about childhood trauma and put to lie the notion that repressed wishes from waking life were the stuff of our dreams. After all, everyday waking life in the 70s was a life already populated by dream characters. From the Village People to HR Puffnstuf, the 70s were a dreamtime, so Freud couldn’t have been right with his dream theory about day residues and repression. Growing up in the seventies meant you didn’t need a talking cure; instead the way to understand your dreams was to check the TV Guide or thumb through your comic book collection.

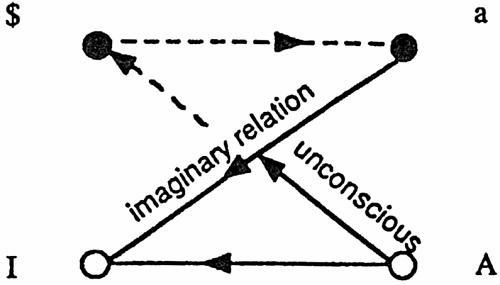

On the other hand, some say that Freud didn’t mean that dreams were brought on by substantial real traumas in the world, or that our dreams emerge from our psychic depths in response to the bad stuff or bad desires we encounter in our waking life, but rather something a bit more twisted than that. For example, in his new book Less Than Nothing, for example, the psychoanalyst Slavoj Zizek interprets Freud’s description of dream-work from Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams.

“[For Freud] the paradox is that this dream-work [or the mental process that hides the true wish that the dream is fulfilling from consciousness] is not merely a process of masking the dream’s ‘true message’: the dream’s true core, its unconscious wish, inscribes itself only through and in this very process of masking in short, it is the process of masking itself which inscribes into the dream its true secret.”

What I take this to mean is that there never really is a pure and simple trauma, and that there is not any one real wish from real life that we can find buried in our dreams, but rather that the trauma and wish is a product of us repressing or masking reality, and this means that we’re as likely to find “reality,” or the real source of our traumas and desires, in a comic book as in any so-called real memory.

For example, one of my earliest childhood traumas can be found in the Jack Kirby Captain America Omnibus I mentioned above. I owned Captain America and Falcon #194, a comic book entitled “Trojan Horde,” when I was only six. It was a cliff hanger, part of a long story arch, and never getting to the end of the story created an itch that I had to keep scratching. I read this issue many times.

Captain America and Falcon face an authoritarian conspiracy. We’re told that the enemy is impossible to imagine or picture. All the good guys at SHIELD know is that these enemies want to bring madness to America. That is the conspiracy’s gift horse. The bad guys have created madness bombs that will cause the usually tranquil and patriotic people of the USA to transform themselves into riotous mobs.

There are three different types of bombs:

This is a bomb that can bring down a small town like Mayberry or Gary, Indiana.

2) The dumpling:

A bomb that can destroy a large city like New York city or Chicago.

3) The Big Daddy:

This bomb can take down the whole country. Captain America’s mission is to stop Big Daddy from going off during the bicentennial festivities.

To use Freud’s dream theory to understand a comic book we have to examine the implications in the details. Regarding these bombs, the first thing that is obvious is that two bombs are also foods, and these two smaller bombs aren’t real threats, but can easily be consumed or absorbed. The real danger is the final bomb named Big Daddy.

Of course these bombs also make a family. A peanut is slang for a baby or a child, whereas the word dumpling is slang for breasts or for a woman, and the Big Daddy is just what it says it is. As it is drawn by Kirby, the Big Daddy is the only bomb that is a phallic tube with a transparent top. We can see inside the head of Big Daddy, can see his mechanical brain. While the peanut and the dumpling are completely opaque, the Big Daddy’s exterior includes a window that let’s us see into Big Daddy’s mind.

In order to fight the conspiracy, to stop Big Daddy, Captain America goes underground. Cap’ and Falcon stop off at a Top Secret bunker where U.S. government operatives can help in the fight by inoculating them against Big Daddy with brain blasts of their own. The helmet/headset Captain America wears is reminiscent of or resembles the silver and purple shells around the mad bombs, and Falcon even mentions this, saying:

“My guess is that the enemy has all this too.”

The brain blasts they receive nearly kill the heroes. They are knocked unconsciousness and the perspective shifts. What follows Captain America falling into unconsciousness is a segment wherein the villains, the people of the conspiracy, are revealed:

“In an exclusive suburb somewhere in the Heart of the land ”

The villain is preparing for the Bicentennial and admiring himself in a mirror, enjoying the 18th century costume he’s picked out, and touching the powdered wig he’s wearing, adjusting it. The villain is an aristocrat and wants America back. The villain is a man named Taurey whose family were members of the aristocracy in the time of the American revolution. Taurey is sick of democracy and wants what he considers his birthright.

“We Taureys have no need for money! We were born rich! We were born to power!”

It’s worth noting that the villain looks like he might be one of our founding fathers. Taurey looks a bit like George Washington who also powdered his hair and who was also a member of the landed aristocracy.

After this we return to Captain America and Falcon and find them apparently naked in bed together. However, in one of the panels it’s made clear that they are in two separate single beds set side by side, and they aren’t naked but merely in their underwear. In any case, Captain America is awake and complaining about the strange dream he’s had. He’s dreamt about his ancestor from the American Revolution, a great, great, grandfather named “Steven Rogers.” And the fact that this ancestor was discussed at length by the villain in the preceding panels gives us the impression that Captain has had a premonition, or perhaps that he has dreamt the villain’s scenes all together.

Captain America and Falcon start to argue over whether Captain’s ancestor should be admired or not. Falcon claims that men like Rogers owned slaves and weren’t to be admired while Captain says that the revolution represents a turning away from injustice.

“It took 200 years, but this country has grown up,” Captain America says.

“Jive! It’s still trying, friend. I’ll stake my life on that,” Falcon replies.

The next panel depicts a bespectacled doctor walking in the door. The words in his speech balloon read:

“That’s what you are doing, Falcon! You can’t let it go down the drain, when our nation is making good on its promise to all men.”

The problem, the doctor tells them, is that the enemy they’ll be facing will be trying to beat the superheroes from the inside out. All of Falcon and Captain America’s strength will be for naught if the enemy succeeds in reaching inside and “shaking us up, real good” as Falcon puts it. The only hope is that the U.S. government has immunized the heroes against the conspirators’ mind weapons.

So, what does it all mean?

Well, putting the personal history of the artist and writer Jack Kirby to the side, ignoring what secret wish he might have been fulfilling here, what’s obvious is that this was working out a solution for the trauma of the 70s, a trauma that the comic book acts out. The trauma was about both the inequities depicted in the comic book and the mass resistance to these inequities, and the wish that this story fulfills is for social equality and quiescence both. The wish is that equality could be established without having to suffer through madness, and this wish is fulfilled in the way that dreams can fulfill such wishes. That is, it fulfills the dream strangely and creates its traumatic wish even as it tries to fulfill it.

Captain America and Falcon #194 assures the reader that the problems of 70s America weren’t endemic to America, but came from the outside. The wish is fulfilled by the villain, the conspiracy. But to really understand this comic book and its message, we have to ask not only what wish was fulfilled, but who was fulfilled. That is, who has to be propped up or forgiven in order for Captain America to get what he wants?

“No wonder these poor devils can’t think or talk,” Captain America says toward the end of issue. “They’re victims of prefrontal lobotomies and glandular changes!”

This comic book wants to let We The People off the hook. We masses must be kept innocent and dumb because if we were ever to face our collective responsibility for our predicament, we’d go mad.

In the final panels, Captain America exposes his real desire. He puts on his mask, picks up his shield, and looks out toward the readers of the comic book.

“In the name of all good men—who love freedom and will fight to keep it—let’s put an end to this nest of rats!” he proclaims.

It doesn’t take a shrink to figure out what that means.

Douglas Lain is a fiction writer, a “pop philosopher” for the popular blog Thought Catalog, and the podcaster behind the Diet Soap Podcast. His most recent book, a novella entitled “Wave of Mutilation,” was published by Fantastic Planet Press (an imprint of Eraserhead) in October of 2011, and his first novel, entitled Billy Moon: 1968 is due out from Tor Books in 2013. You can find him on Facebook and Twitter.